This article was originally published a while back at

The Daily Banter, a left-leaning political blog worth checking out. They have some reasonable people over there, and are good writers to boot.

In the following piece, I highlight a case example of a type of entirely-useless assertion that is made far too often in the wake of tragedy. The broad assertion: A person's beliefs cause them to behave in certain ways. The specific example here is someone who murdered nine innocent black Americans in a South Carolina church in June 2015. Many asserted in the aftermath that the killer's racism motivated him to murder - I think this explanation is insufficient and incorrect.

Why Dylann Roof's Racism Did Not Cause the Massacre in Charleston

Last weekend, neuroscientist and popular author Sam Harris

tweeted, “Is there anyone who doubts that the odious Dylann Storm Roof was

motivated by his (racist) beliefs?” To which I reply: Yes, I doubt this very

much. I do not believe that Roof murdered those people because he is racist. In

fact, I consider it actively harmful to posit this as an explanation for the

tragedy that took the lives of nine innocent black Americans.

Before I get drowned in a flood of hate mail, let me clarify

things a bit. First, I think it is very clear that Roof is a virulent racist. A

huge amount of evidence indicates that he holds truly repugnant views on race,

especially with respect to black people. His crime was an act of domestic

terrorism, and unless something truly unexpected emerges during the legal

process, he should be thrown in prison for the rest of his life. However, his

racism did not cause him to murder those people. Like his crime, his racism is

not a cause, but an effect. At this

time, we should be asking about the nature of the shared cause for both, and

considering how this analysis may help prevent similar tragedies from occurring

in the future.

Human behavior can seem extraordinarily complex. However, in

a scientific analysis, we can simplify the relevant general processes that

govern behavior to less than a handful of items. For our purposes here, let us

consider “Behavior and Belief” as the middle link in a three-link chain. The

first link is “Environment and Culture,” and the last is “Consequences.”

|

| Now I know my A, B, C's... |

Just like with a physical chain, when you move a single

link, you also tend to move the others. Reward (or reinforcement) and

punishment are examples of consequences that change behavior. Rewards are

offered for good behavior as a way to increase the likelihood of similar good

behavior happening in the future; punishments are threatened to reduce the chances

of unwanted behavior occurring. On the other hand, environments serve to provide

a context for the kinds of behavior

that will be reinforced or punished. If you have cheered at the top of your

lungs while attending a raucous sporting event, but would never dream of doing

so at a somber funeral, you recognize the importance of environments in

controlling your behavior. When we talk about a culture, we are merely describing a social environment that serves

to set the stage for the reinforcement of particular sorts of human behavior.

For example, someone invoking “gun culture” in America is really talking about

the vast web of human interaction that provides cover and, ultimately,

reinforcement for those who would buy, sell, collect, discuss, and shoot guns.

That our behavior is a necessary product of both its

consequences and its antecedent environmental conditions is critically

important to remember when we want to improve our lot in this world, because it

is only by manipulating these links

that we can change human behavior.

The consequences for Dylann Roof’s actions could not be more

dire for him. By murdering those people, he has probably ensured that he will

spend his remaining years in prison, and may even face execution. It is

difficult to imagine harsher consequences for one’s actions, and yet the

behavior still happened. Roof is not

insane – there can be little doubt that he knew that he would probably be

caught, and knew that his life was effectively coming to an end with his

actions. In fact, that many terrorists (e.g., suicide bombers, mass shooters)

kill themselves in their attacks could be seen as an acknowledgment that their

lives are effectively over, that only terrible things await them. We probably

cannot and definitely should not design punishments that are harsher than

death. So, to reduce violent crime and terrorism, what are we to do?

Our only option is to change the environments that give rise

to violent crime. Cultures that encourage profligate use of firearms, distrust of

education, and hatred of minorities will be much more likely to have a Dylann

Roof emerge from them than cultures where any of those pillars is missing. If

you remove the antecedent conditions that would give rise to objectionable

behavior, you prevent that behavior from ever occurring. Roof’s beliefs did not

and do not matter in a causal analysis. At most, his racism is an indicator, a

symptom of a sick world from which he emerged. Arguing about beliefs is

unproductive. Instead, we should talk about the conditions that caused Roof to

behave as he did and believe as he

does.

It is perverse that so many people would deny or obfuscate

the role of culture in causing tragic events like the Charleston massacre. When

we see Fox News talking heads blatantly ignore the topic of race relations in

America as a determining factor in this tragedy, we are watching people essentially

trying to prevent cultural change with respect to race. When pundits claim that

crimes like Charleston are acts of the mentally ill, or are “isolated” or

“senseless” incidents, they work to prevent clarity on the causes for the

crimes. Guns rights advocates often go a step further, suggesting that culture is important, but arguing that an expansion of their culture is needed. Simplistic aphorisms like, “an armed

society is a polite society,” and “guns don’t kill people, people do” are intonations

of a culture that is working to preserve itself. That platitudes like these are

demonstrably untrue is of little consequence to the group’s members, as what

really matters is that the words are effective at perpetuating a cultural

message beneficial to their aims.

|

| Behold: A necessary product of a particular kind of environment. |

If we can blame a man for a crime, if we can fully blame a

person’s mental state or mental illness, it absolves a culture from responsibility.

It is easy to see why we tend to blame the individual. If a crime is the sole

responsibility of a person, we have many ways to deal with the issue – an

individual may be fined, shamed, institutionalized, imprisoned, or executed,

any of which is usually easy enough to implement. After punishing the criminal,

we can heartily congratulate ourselves on effectively addressing the problem.

However, if a person’s criminal actions are the necessary product of a larger

causal force, the problem we are looking to fix becomes much, much more

challenging. Punishing the criminal may help prevent some unlawful actions in the

future (see chain link #3), but a maximally effective technique must also address the issue of the complex

environment that gave rise to the behavior in the first place. Humans tend to

prefer simple answers to complex ones. Some of us have a stronger preference

than others.

Saints and monsters do not emerge from nothingness, but

instead are built by their environments. By building a better world, we can

banish monsters like Dylann Roof from the human experience. To do so, we must

not be distracted by those who would muddy the waters. We must not be confused

by fervent appeals to a kind of freedom that none of us has. We must not talk

of beliefs in causing behavior, but instead talk about how beliefs are built.

By understanding and accepting our necessary, intermediate role between culture

and consequences, we understand how we might change human behavior for the

better.

______

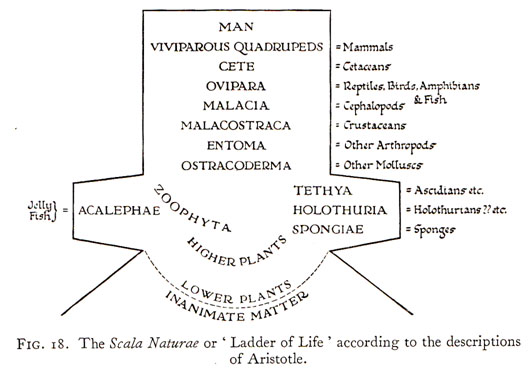

P.S. I got some feedback regarding this post when it was first published suggesting that I had, perhaps, a too-narrow view on what constitutes causality in a behavioral analysis. I have thought about it, and I don't think that the criticism is valid. At a later date, I will attempt to explain why Aristotle was wrong about causality and again explain why teleology (i.e., final causes) have no place in a proper understanding of the universe.

.jpg)