About a week ago at a very early hour, I was sitting with my laptop, clicking through headlines on my usual circuit of blogs, social media, and news sites. I checked in on the Cubs score. I read tweets from people experiencing the annual Perseid meteor shower and sighed; unfortunately, the skies above me were cloudy that morning. Even if they weren't, there was a good chance I wouldn't have seen much, due to significant light pollution from D.C. I half-heartedly scanned a few political pieces on the presidential primary races. Hillary Clinton. Bernie Sanders. Donald Trump. Oh, great, Scott Walker is spending a few hundred million dollars on a new sports stadium in Milwaukee.

This is a normal pattern. It's usually just a matter of time before something reaches out and grabs my attention with both hands.

And then I came across it: NBC News reporting on a new study published in Nature, about the sequencing of the octopus genome. Apparently, this is the first time that it has been done in any cephalopod. Very cool.

Unfortunately, there's some added information within the article about the intelligence of octopuses. A biology graduate student on the paper is quoted as saying that the cephalopods are "remarkable creatures." Octopuses "can camouflage themselves with skin that can change its color and texture." The animals also have "large, elaborate brains that allow them to be active predators with complex behaviors."

There are a couple of enormous problems with this characterization of the octopus. They both revolve around a single broad issue: They suggest a basic misunderstanding of what animals are.

I cannot fault the graduate student for the error. It is an incredibly pervasive one, so much so that many researchers would scarcely have paid it any mind in the first place. The student was being quoted for a popular piece within the mainstream press. This requires a relaxation of the usual scientific jargon, but this can be costly. I do not wish to pick on this student specifically, but rather use her words to highlight faulty practice within science communication that is in desperate need of correction. This post will address the claim that octopuses are remarkable creatures; the next will address the issue of teleology as an explanatory tool.

First: Are octopuses remarkable creatures?

To the extent that one can and may remark on octopuses, this is doubtlessly true. But to suggest that they are somehow unusual is certainly untrue. The truth is that there is nothing inherently more remarkable about the octopus than about any other kind of animal. People, scientists included, are not impartial observers of the natural world, but are packed with biases that color their judgments. Yes, the octopus has morphology and a behavioral repertoire that are each terribly fascinating. However, this reflects nothing uniquely important about the octopus, but instead tells us something about humans.

Are there species of animal out there that are not remarkable? I doubt anyone can reasonably explain why squirrels are not remarkable. Or pigeons. Or hermit crabs, or hummingbirds, or earthworms. The members of any extant species are necessarily the product of billions of years of evolution, and in a very important biological sense, are all exactly equally suited to their ecological niche. What we observe are the tiny, existent portions of a theoretical distribution of all possible organisms, which itself is characterized by a nearly infinite distribution of possible genomes. Every species has unique characteristics within its members; indeed, each must in order to be defined as a species in the first place (pay no mind to how squishy the definition of "species" really is). Every animal of every species is characterized by a combination of both morphological and behavioral adaptations that have been shaped by distinct environments across evolutionary time.

If every species is remarkable, then none are.

Octopuses are charismatic animals only in the sense that they appeal to the human animal, and not for any reason owing to their specific nature. There are many reasons why this might be so, but in the absence of scientific data one can only speculate. It is probably important that they make fairly rare appearances in most humans' lives. Aside from a relative handful of biologists, almost no one has frequent interactions with cephalopods. Additionally, that they appear (to us) to behave in a manner akin to human intelligent behavior almost certainly renders them endearing. Consider them alongside other well-loved, charismatic animal species, like bonobos, dogs, and elephants.

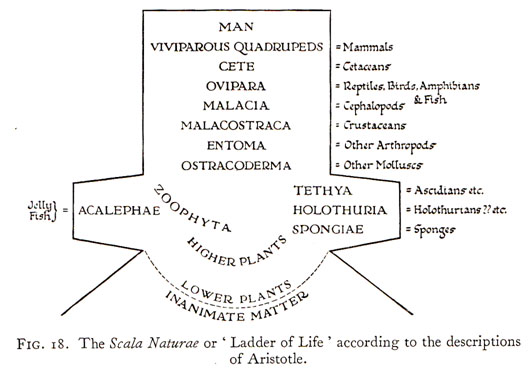

In summation of this point: It is important that scientists openly embrace that the entirety of Earth's biosphere is necessarily equivalent when it comes to the fundamental machinations of evolution. Speaking as a layperson, it is not a problem to pick favorites. Personally, I am a dog lover, and entertained the idea of owning a colony of rats. I also have a fascination with jumping spiders that borders on the unhealthy. However, speaking as a scientist, it is at best slippery to assert that some animals are more intelligent than others - if you doubt this, try to concretely and objectively define intelligence to a friend. When we humans apply the term to nonhuman animals, we typically are just referencing how like humans they seem to behave. It does nothing to improve the public's understanding to assert that certain species are somehow more "remarkable" than others. If anything, doing this serves to reinforce an Aristotelian-style hierarchy at which Homo sapiens sits at the top. Such a view has been scientifically outdated since Darwin's time, but has persisted in our common language.

|

| This is very wrong. |

So Earth is like a big 'ol Lake Woebegone, where all of Darwin's children are above average.

ReplyDeleteThat we are all here, that we are the tiny fraction (both of possible species and of possible individuals within species) that got to exist in reality... I'd say that makes us all equally "above average," in an odd ontological sort of way.

ReplyDelete(I recognize your comment was probably tongue-in-cheek)